S: And what is the organ with which we see the visible things?

I: The sight, he said.

S: And with the hearing, I said, we hear, and with the other senses perceive the other objects of sense?

I: True.

S: But have you remarked that sight is by far the most costly and complex piece of workmanship which the artificer of the senses ever contrived?

I: No, I never have, he said.

S: Then reflect; has the ear or voice need of any third or additional nature in order that the one may be able to hear and the other to be heard?

I: Nothing of the sort.

S: No, indeed, I replied; and the same is true of most, if not all, the other senses –you would not say that any of them requires such an addition?

I: Certainly not.

S: But you see that without the addition of some other nature there is no seeing or being seen?

I: How do you mean?

S: Sight being, as I conceive, in the eyes, and he who has eyes wanting to see; colour being also present in them, still unless there be a third nature specially adapted to the purpose, the owner of the eyes will see nothing and the colours will be invisible.

I: Of what nature are you speaking?

S: Of that which you term light, I replied.

I: True, he said.

S: Noble, then, is the bond which links together sight and visibility, and great beyond other bonds by no small difference of nature; for light is their bond, and light is no ignoble thing?

I: Nay, he said, the reverse of ignoble.

S: And which, I said, of the gods in heaven would you say was the lord of this element? Whose is that light which makes the eye to see perfectly and the visible to appear?

I: You mean the sun, as you and all mankind say.

S: May not the relation of sight to this deity be described as follows?

I: How?

S: Neither sight nor the eye in which sight resides is the sun?

I: No.

S: Yet of all the organs of sense the eye is the most like the sun?

I: By far the most like.

S: And the power which the eye possesses is a sort of effluence which is dispensed from the sun?

I: Exactly.

S: Then the sun is not sight, but the author of sight who is recognised by sight.

I: True, he said.

S: And this is he whom I call the child of the good, whom the good begat in his own likeness, to be in the visible world, in relation to sight and the things of sight, what the good is in the intellectual world in relation to mind and the things of mind.

I: Will you be a little more explicit? he said.

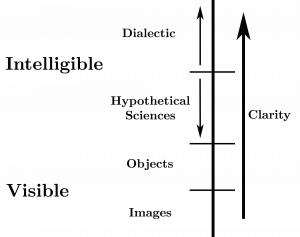

S: Why, you know, I said, that the eyes, when a person directs them towards objects on which the light of day is no longer shining, but the moon and stars only, see dimly, and are nearly blind; they seem to have no clearness of vision in them?

I: Very true.

S: But when they are directed towards objects on which the sun shines, they see clearly and there is sight in them?

I: Certainly.

S: And the soul is like the eye: when resting upon that on which truth and being shine, the soul perceives and understands and is radiant with intelligence; but when turned towards the twilight of becoming and perishing, then she has opinion only, and goes blinking about, and is first of one opinion and then of another, and seems to have no intelligence?

I: Just so.

S: Now, that which imparts truth to the known and the power of knowing to the knower is what I would have you term the idea of good, and this you will deem to be the cause of science, and of truth in so far as the latter becomes the subject of knowledge; beautiful too, as are both truth and knowledge, you will be right in esteeming this other nature as more beautiful than either; and, as in the previous instance, light and sight may be truly said to be like the sun, and yet not to be the sun, so in this other sphere, science and truth may be deemed to be like the good, but not the good; the good has a place of honour yet higher.

I: What a wonder of beauty that must be, he said, which is the author of science and truth, and yet surpasses them in beauty […]