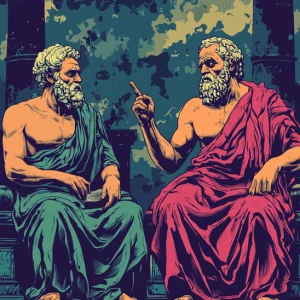

Lines 6d – 8a

Euthyphro: What is dear to the gods is holy, and what is not dear to them is unholy.

Socrates: Excellent, Euthyphro, now you have answered as I asked you to answer. However, whether it is true, I am not yet sure; but you will, of course, show that what you say is true.

Euthyphro: Certainly.

Socrates: Come then, let us examine our words. The thing and the person that are dear to the gods are holy, and the thing and the person that are hateful to the gods are unholy; and the two are not the same, but the holy and the unholy are the exact opposites of each other. Is not this what we have said?

Euthyphro: Yes, just this.

Socrates: Well then, have we said this also, that the gods, Euthyphro, quarrel and disagree with each other, and that there is enmity between them?

Euthyphro: Yes, we have said that.

Socrates: But what things is the disagreement about, which causes enmity and anger? Let us look at it in this way. If you and I were to disagree about number, for instance, which of two numbers were the greater, would the disagreement about these matters make us enemies and make us angry with each other, or should we not quickly settle it by resorting to arithmetic? […]

But about what would a disagreement be, which we could not settle and which would cause us to be enemies and be angry with each other? Perhaps you cannot give an answer offhand; but let me suggest it. Is it not about right and wrong, and noble and disgraceful, and good and bad? Are not these the questions about which you and I and other people become enemies, when we do become enemies, because we differ about them and cannot reach any satisfactory agreement?

Euthyphro: Yes, Socrates, these are the questions about which we should become enemies.

Socrates: And how about the gods, Euthyphro. If they disagree, would they not disagree about these questions?

Euthyphro: Necessarily.

Socrates: Then, my noble Euthyphro, according to what you say, some of the gods too think some things are right or wrong and noble or disgraceful, and good or bad, and others disagree; for they would not quarrel with each other if they did not disagree about these matters. Is that the case?

Euthyphro: You are right.

Socrates: Then the gods in each group love the things which they consider good and right and hate the opposites of these things?

Euthyphro: Certainly.

Socrates: But you say that the same things are considered right by some of them and wrong by others; and it is because they disagree about these things that they quarrel and wage war with each other. Is not this what you said?

Euthyphro: It is.

Socrates: Then, as it seems, the same things are hated and loved by the gods, and the same things would be dear and hateful to the gods.

Euthyphro: So it seems.

Socrates: And then the same things would be both holy and unholy, Euthyphro, according to this statement.

Euthyphro: I suppose so.

Socrates: Then you did not answer my question, my friend. For I did not ask you what is at once holy and unholy; but, judging from your reply, what is dear to the gods is also hateful to the gods. And so, Euthyphro, it would not be surprising if, in punishing your father as you are doing, you were performing an act that is pleasing to Zeus, but hateful to Cronus and Uranus, and pleasing to Hephaestus, but hateful to Hera, and so forth in respect to the other gods, if any disagree with any other about it.